What Irish Americans Can Learn from the Irish Vampire Remmick in Ryan Coogler's Masterpiece "Sinners"

The Irish and African American Communities have Shared a Close but Contentious Relationship. Understanding Irish History and How the Irish Became White Adds Another Layer to "Sinners."

To show my appreciation for your steadfast understanding, patience and support as my inflamed and spastic back muscles heal, I am offering 60% off forever on new paid subscriptions and upgrades until May 31.

I want to celebrate Harvard University for not bending its knee to the Mump-Nazi Reich. Until May 31, I am offering faculty, staff and students with an .edu e-mail 50% off forever.

I hope more educational institutions, especially those in higher education, learn from Harvard’s and history’s example of colleges and universities remaining bold against tyranny and autocracy.

Content Warning: Spoilers for “Sinners”; offensive racial slurs

"I am the voice of your history

Be not afraid, come follow me

Answer my call and I'll set you free" —Eimear Quinn, “The Voice”

"The oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves to become oppressors." —Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed

During her Critics Choice Award acceptance speech, Demi Moore, who won for her astonishing performance as Elisabeth Sparkle in The Substance, declared that “horror films . . . are overlooked and not seen for the profundity that they can hold.” Like other resonant art, Sinners requires multiple viewings. With each viewing, the viewer can take in the full meaning behind NAACP Image Award-winnning and acclaimed auteur Ryan Coogler’s images, sounds, historical references, themes and social commentary.

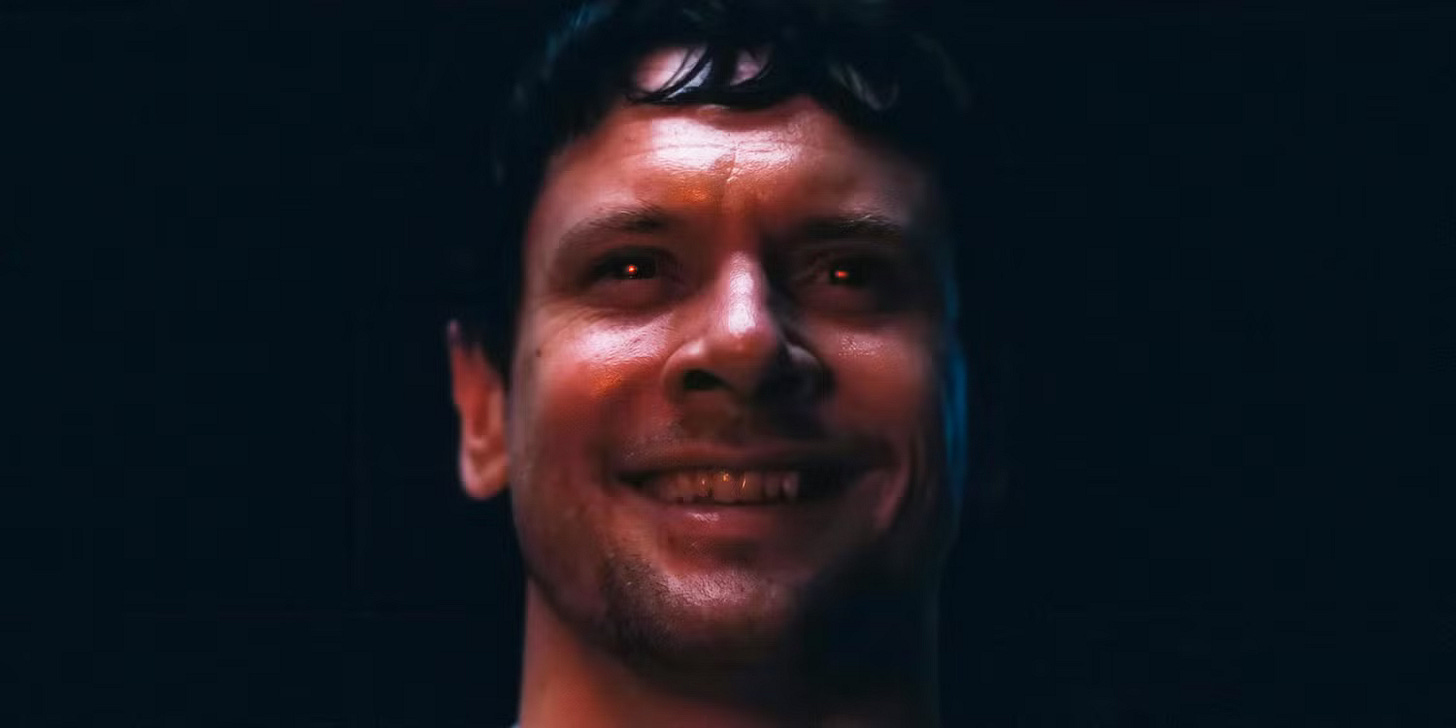

One character to further examine is the Irish vampire Remmick. He’s not a binary horror or racial villain. Coogler in his wisdom instead creates a nuanced character we all must grapple with.

By Coogler using vampirism and making Remmick Irish, he emphasizes the shattered solidarity between African Americans and Irish Americans. He also uses Remmick to acknowledge cultural appropriation by the white race to benefit their own needs and wants.

Most of all, Remmick underscores how assimilation into self-serving whiteness damages then erases ethnicity, language and culture. By mixing multiple narrative genres within his themes of race and violence, Coogler reveals a brutal American truth.

Coogler via Remmick tells my fellow Irish Americans and I that we not only have to learn more about our history and culture but how our ancestors broke solidarity with African Americans. We must learn why and how our ancestors abused and exploited African Americans in order to achieve whiteness and racial privilege.

Aurora Levins Morales wrote that we are not responsible for our ancestors’ sins. What we are responsible for is acknowledging them and not committing the same sins again. Once this is done, us Irish Americans can rebuild allyship and move from allyship into becoming accomplices and co-conspirators.

Sinners is not Remmick’s story but the story of Smoke, Stack and the African American community of Jim Crow Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1932. Coogler sets Sinner’s most powerful scene in Smoke and Stack’s juke joint.

Like jazz, the blues stands as an original American art form that has influenced musicians across the world of various races. The one-shot scene reveals how Smoke and Stack’s cousin Sammie’s miraculous original blues song “I Lied to You” rips the veil segregating past, present and future. It also showcases Black liberation and freedom.

Once Sammie’s notes and lyrics tear time’s curtain, the audience takes in how African music influenced the blues and how both influenced funk, hip hop, rap, rhythm and blues and, of course, rock and roll. The movie’s intro. cards and narration explain how the music of West Africa, ancient China and ancient Ireland are so powerful that it can erase “the barriers between the living and the dead.”

Later in the film, we learn that Irish native Remmick became a vampire in fifth century Ireland. His family and friends have long vanished from the earthly dimension, and the isolated and lonely Remmick longs to be with them once more. He needs community to accomplish that along with the added power of Sammie’s music.

By turning Sammie into a vampire and co-opting his blues music along with his own Irish folk and rebel music, Remmick knows the combined power will integrate past, present and future. Hence Remmick weaponizes his whiteness, his own oppression and his own tortured Irish identity to belong to the juke joint community.

He tells Sammie and the other juke joint patrons they can start and build a new community free from racism and pain. Yet all Remmick accomplishes is the spilling of literal and metaphorical blood.

That blood drowns any unity and empathy between the Irish and African races. Remmick wants to use Sammie and the blues to vanquish his own grief and escape his own pain. All he does, however, is create an undead, hivemind and bloodthirsty coven that assimilates.

Delroy Lindo who plays the film’s blues pianist and harmonicist Delta Slim concurs. After he tells That Grape Juice’s Sam A. how art can transfigure pain, he underscores the film’s message of community and how knowing and respecting one’s history and identity are essential to embracing truth.

Two other truths Coogler addresses in “Sinners” are the kinship between the Irish and African American communities and how pain shaped and inspired the blues and Irish folk and rebel music. A good example of the kinship is when Frederick Douglass traveled to Ireland during The Great Hunger. His Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave had just been published in Ireland, and he took in the country and The Great Hunger on his book tour.

On his visit to Dublin, he remarked it was the first time in his life where he could walk unafraid among white men: “I saw no-one that seemed to be shocked or disturbed by my dark presence. No one seemed to feel himself contaminated by contact with me.”

In his letter to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison after calling out America’s hypocrisy and refusal to address its original sin of chattel slavery, he described and reflected on The Great Hunger’s horror:

I believe that the sooner the wrongs of the whole human family are made known, the sooner those wrongs will be reached. I had heard much of the misery and wretchedness of the Irish people, previous to leaving the United States, and was prepared to witness much on my arrival in Ireland. But I must confess, my experience has convinced me that the half has not been told. I supposed that much that I heard from the American press on this subject was mere exaggeration, resorted to for the base purpose of impeaching the characters of British philanthropists, and throwing a mantle over the dark and infernal character of American slavery and slaveholders. My opinion has undergone no change in regard to the latter part of my supposition, for I believe a large class of writers in America, as well as in this land, are influenced by no higher motive than that of covering up our national sins, to please popular taste, and satisfy popular prejudice; and thus many have harped upon the wrongs of Irishmen, while in truth they care no more about Irishmen, or the wrongs of Irishmen, than they care about the whipped, gagged, and thumb-screwed slave. They would as willingly sell on the auction-block an Irishman, if it were popular to do so, as an African.

Nonetheless, Douglass stressed that the injuries and pain British colonialism inflicted upon the Irish did not equal the injustice and evil caused by chattel slavery; instead Douglass noticed “the parallels” between the Irish and African Americans.

Another harsh truth Coogler alludes to in his narrative is how capitalism, assimilation and white supremacy drove a wedge between both communities and made one fight and oppress the other. Ron Cassie in his 2023 Baltimore magazine article on Douglass and his time in Ireland acknowledges, “It is no small irony that Douglass’ success in Ireland came on the heels of his often-abusive treatment by Irish immigrants in the U.S., many of whom saw free Blacks as competition for jobs. Not to mention, his Baltimore enslaver, Thomas Auld, was an Irish immigrant.”

Remember the protagonist of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind is named Scarlett O’Hara. Irish immigrants also contributed to the U.S. Constitution’s Three-Fifth’s compromise and worked as plantation overseers. The oppressed became the oppressors.

in his 2018 article in The Root “When the Irish Weren’t White” asserts,Treated as an inferior race under British rule in Ireland, many Irish immigrants were sympathetic to the plight of black Americans. [Noel] Ignatiev [author of How the Irish Became White] described how the Irish in America came to be accepted as white, arguing that the price they paid for this transformation was to adopt white attitudes toward blacks. He regarded the incorporation of the Irish into whiteness as a tragedy and a missed opportunity for common struggle. He could have told a similar story about numerous immigrant groups who paid a similar price for admission to the white race, but he found the Irish example particularly instructive because of their history of radical resistance to oppression.

Along with noticing how racism structured laws and American society, Harriot points out that the Irish had the benefit of our fair complexion to accomplish the whiteness assimilation. To seal their acceptance and “death” into the vampirism of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant America, the Irish had to reject their language (here’s a quick tutorial on the Irish alphabet), identity and culture. But we have to remember as Harriot points out,

“[w]hiteness” isn’t real. Ultimately, race is a social construct, and “white” is just some dumb shit that people made up a long time ago to build a fence around their idea of self-supremacy. The Irish didn’t suddenly calm down, put down the Guinness, put their noses to the grindstone and work their way into an exclusive club. They had the same historical trajectory in America as the Polish, Italians and Jewish people. Their melanin-less skin just afforded them an opportunity to blend in that black people will never get.

Anti-racist educator and eternal bad-ass Jane Elliot stresses that the concept of “race” did not begin until the brutal Spanish Inquisition during the fifteenth century. Once that persecution of Jews, Muslims and “heretical” Catholics and Christians began, the false idea of white supremacy developed.

Because of The Doctrine of Discovery, which The Vatican has only “repudiated” and not rescinded, soon Europe’s colonization overtook and ravaged the world. This is why Susan Sontag exclaims in her 1967 Partisan Review essay, “The white race is the cancer of human history.”

However in fifth century Ireland when Remmick became a vampire, the social construct of race did not exist. Coogler knows and understands the history of the Irish and Irish émigrés. During his interview for Filmmaker Toolkit, Coogler acknowledged his love and respect for Irish culture and history. From that he developed Remmick’s character and backstory:

I’m obsessed with Irish folk music, my kids are obsessed with it, my first name is Irish. I think it’s not known how much crossover there is between African American culture and Irish culture, and how much that stuff is loved in our community.

. . . .

It was very important that our master vampire . . . was unique as the situation. It was important to me that he was old, but also that he came from a time that pre-existed these racial definitions that existed in this place that he showed up in. He would be extremely odd, and [the racial dynamics of 1932 Mississippi] would all seem odd to him, but he would see it for what it was and offer a sweet deal, and that the music was just as beautiful.

Nadira Goffe’s Slate article analyzes how the white villain dynamic carries a depth beyond the one-dimensional good-versus-evil narrative; it ultimately reveals the insidiousness of white supremacy and colonization:

One reading of this film is that the villains are the vampires: Just picture, three bone-chilling white vampires standing at the entrance of this Black establishment, asking to be let in. But that reading ignores the specificities Coogler imbues his portrayal of the undead with, leaving the audience with a more nuanced message. A less ambitious movie would build its binary of good and evil off the chilling imagery of the vampires at the door, simplifying the matter to “vampires = white predators” and “humans = Black victims and heroes.” Thankfully, Coogler is not that kind of filmmaker, and Sinners is not that kind of movie. If the movie’s white, bloodthirsty monster is not the true villain of Sinners, then who—or what—is? The answer lies in the film’s interrogation of the lengths you’d consider going to escape structural torment. The greatest evil here is white supremacy, the system of structural racism and bigotry underlining all aspects of life in 1930s Mississippi.

In Coogler’s supernatural vision, the vampires are ultimately presented in a sympathetic light, expressing solidarity in grief and loss with the preyed-upon Black characters—furthermore, there’s an even more sinister power to fear in this film. Remmick positions himself as an ally to the oppressed, rather than yet another oppressive force, by revealing a worse evil than himself. He reveals to Smoke and the others that the white man who sold the twins the sawmill is the leader of the local KKK chapter, who—despite the twins’ asserting that their money must also buy them protection from the Klan—plan to show up the next morning, burn down the property, and murder anyone left inside. Of course, this could just be a fearmongering tactic—if Remmick weren’t proven right in the end.

But Sinners’ humanization of Remmick doesn’t stop there. The fact that Remmick is Irish—as signified by his slight accent and by a truly spine-tingling Irish folk number he leads the freshly turned vampires in performing—is key. Irish people in America were not considered racially white in the way that they are today; they have a history that shares similarities with that of Black people, involving colonialization, religious persecution, and more.

The late Sinéad O'Connor's Sean Nós version of John Gibbs’s “Irish Ways and Irish Laws” provides a haunting and concise history of Ireland and the colonialism, oppression and violence the island’s inhabitants lived under for centuries.

Coogler provides more information about Remmick on the film's soundtrack page on Spotify. A newspaper article from a 1911 issue of The Boston Daily Journal reveals that Remmick arrived in the United States on an Irish immigrant ship where he slaughtered and fed upon the other Irish immigrants. Here Coogler alludes to The Demeter section in Dracula penned by Bram Stoker, another Irishman.

The Boston Daily Journal article mentions witnesses saw Remmick flee from the ship as the sun emerged. Since he came over to The States in 1911, this means Remmick witnessed not only the Christian evangelization of pagan Ireland but the earlier invasions and oppressions “Irish Ways and Irish Laws” list.

Later Remmick experienced English and British colonialism. This includes the failed Irish Rebellion of 1798, an event that inspired the Limerick poet and Irish literature academic Robert Dwyer Joyce to compose the folk song “The Wind that Shakes the Barley.” Lisa Gerrard performs the following haunting Sean Nós version.

Arriving in the U.S. in 1911 meant Remmick missed the 1916 Easter Rising and the Irish Republican Army's (IRA) guerrilla warfare that finally drove out the British empire. The Neil Jordan biopic Michael Collins dramatizes how Ireland fought for and ultimately won its independence after seven centuries of English and British colonization.

The rebellion led by the Irish revolutionary and later finance minister of the provisional Irish government Michael Collins created the Irish Free State. The Irish Civil War resulted from the Irish Free State’s establishment, since those who wanted a republic voted against the free state treaty.

Ultimately the Republic of Ireland became official in 1949. Only Northern Ireland remains part of the UK. The rebel song “Come Out Ye Black and Tans” by Dominic Behan, son of Irish revolutionary Stephan Behan, addresses the British empire’s colonialism not only in Ireland but ridicules its methods in Afghanistan and the Zulu Kingdom. At the same time, it extols the IRA's rebellion and strength in fighting the British empire in the early twentieth century.

Though Remmick missed Ireland's independence, he witnessed at night the island's most devastating historical event— The Great Hunger. The Irish diaspora took off in 1820 because of a famine; a new and much more devastating famine ballooned two decades later before, during and after what is now known as The Great Hunger’s worst year Black ‘47.

Today scholars and historical journalists such as Tim Pat Coogan declare The Great Hunger was genocide committed by the British government and worsened by absentee English landlords. Though Remmick would have fed on the dying and desperate beneath the Irish moon, the day’s hellish reality remained after the sun disappeared.

More can be learned about The Great Hunger and the genocide claim in the videos and audio below from The Gravel Institute, Behind the Bastards where host Robert Evans and Hood Politics host Prop do a deep dive and O’Connor’s “Famine.”

Coogler’s knowledge of Irish history continues in his scene with the Mississippi Choctow who hunt Remmick to kill him. As with Sammie, Remmick tried to use the Choctow’s knowledge and respect of nature and spirituality to reach the specters of his long-dead family. Like the Choctow, pagan Ireland also respected and revered nature especially animals. And Like O’Connor wrote and sang in “Famine,” the God the Irish pagans worshipped still existed but was a woman—Ériu.

What makes this scene ironic is that The Choctow donated money to help the Irish during The Great Hunger. In County Cork, people can view the Kindred Spirits monument that signifies the relief the Choctaw people provided despite experiencing their own hardship The Trail of Tears created. Coogler uses the Mississippi Choctow in Sinners to try and kill Remmick because they know he is a vampire and an abomination against nature and humanity.

Coogler also knows that when Irish immigrants came to the United States, they experienced more discrimination and abuse though that abuse and discrimination didn’t rise to what African Americans endured. Like Africans and African Americans though, the United States did not consider the Irish socially “white.”

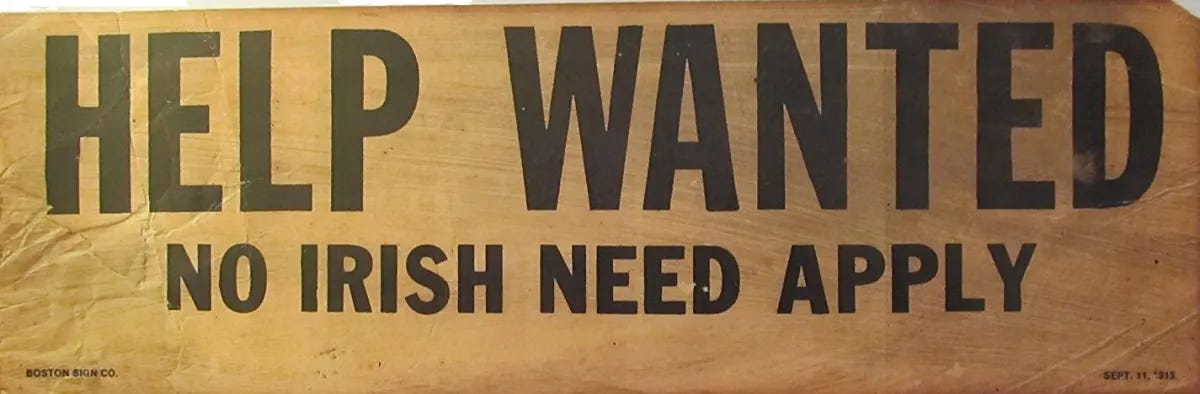

Insults and discrimination directed at the Irish resemble the insults and bigotry now directed to migrants, immigrants and asylum seekers from Mexico, Central America, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Africa and Asia: dirty, disease-ridden, foul, ignorant, criminal, immoral. Signs saying “No Irish Need Apply” frequented 19th century American towns and cities.

Because of this, the xenophobic Know Nothing party formed with anti-Irish and anti-Catholic bigotry and discrimination directing its mission. In the early 20th century, the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Irish Catholics and Catholics overall. Shamefully today some white Catholics align with white nationalism or join the Ku Klux Klan, denying their own history of persecution.

One of the best films to address racism, xenophobia, anti-Hibernianism, whiteness and anti-racism in America’s West is Mel Brooks’s classic comedy Blazing Saddles. Today Brooks’ uproarious and insightful film may have never been made even with the late Richard Pryor co-penning the farcical screenplay.

The second most powerful scene in Sinners is Remmick singing the 19th century Irish folk song “Rocky Road to Dublin” composed by Irish poet DK Gavan. Chills ran through me, and I felt the urge to cry as I watched this scene in the theater. The early lyrics of “off to reap the corn” is Irish slang for finding riches. This mirrors Smoke and Stake’s story of heading to Chicago to work with Al Capone to seek their own fortunes.

With “Rocky Road to Dublin,” Remmick acknowledges and embraces his Irish identity and brogue that he had hidden under a Southern twang to “assimilate” and feed in the Jim Crow South.

According to a thorough and wonderful analysis by RecapDb, this song and Remmick’s Irish dancing acknowledge the oppression he and his fellow Irish faced under English and British rule and with the Irish-immigrant experience. Irish dancing was artistic and cultural resistance against the English and British who worked to erase Irish identity and culture (see the scene below from the The Wind That Shakes the Barley that won the 2006 Palme d'Or).

One of the film’s final scenes resonates as much as Sammie’s “I Lied to You” and Remmick’s “Rocky Road to Dublin.” It is the scene where Sammie and Remmick recite the “Our Father” simultaneously facing each other.

Earlier in Sinners, Delta Slim tells Sammie that the blues was not forced on African Americans like Christianity. Sammie’s father is a Christian pastor who tells Sammie to reject the blues and accept his Christian faith. The blues, he tells Sammie, is evil and will only bring forth evil.

When Christianity came to pagan Ireland, the pagan inhabitants also had the new religion forced on them. Remmick says the “Our Father” does add comfort while it also reminds him of how his land, language and culture were stripped from his father and country by forced Christianity and colonialism.

The only note I would offer Coogler would have been for Remmick to say the “Our Father” in Irish to Sammie. It would have been the final part of Remmick reclaiming his identity.